Prelude to May 7, 1754

Moro Watch Tower (KOTA) Baybay Norte Undated photo c.a. 1930, courtesy of Mr. Ernie Palmos

People call me Boni, short for Bonifacio. Spanish names seemed unnatural for us whom the Spaniards simply call derogatively as Indios. Harder to pronounce Spanish words. Or, just simply too long for our Kinaray-a tongue. I was just 10 years old when the raiders came from the sea. I was terrified. Everyone was. The mere utterance of the word Moro evoked a sense of foreboding, fear and despair. Raiders are aplenty in these islands. Not always Moros. Often, they are marauding bandits of all kinds. Christians and non-Christians, such as the Pintados, Chinese and Japanese pirates. As soon as the bell rang everyone in our village ran for our lives. We knew what each rhythm of the church bell meant. That particular one was the distinct warning that the raiders were coming. Not many of us made it to the safety of the mountains. The raiders came too fast, using the Tumagbok River as their gateway. The elders, the wounded and the very young were butchered like pigs, mercilessly cut to pieces with the kampilan or the kris, the long wavy swords of the Moro raiders. They were simply useless for the slave trade and the long voyage back to their homeland. My father and mother were among the unlucky ones. When others found me deep in the jungle I was told that the other young men and women were taken to be sold in the slave markets of Sandakan and even as far away as Batavia in the island of Java. Even now I do not know where Sandakan or Java is. I have not gone beyond the boundaries of Miagao.

My Uncle, Nicolas Pangkug, the first capitan of Miagao, finished the construction of our church in 1731 so that the Spanish priests from Oton would finally come to serve the religious needs of this town. In the year of our Lord 1741, the raiders came. They raped, killed, looted and burned our church!

My Uncle, Nicolas Pangkug, the first capitan of Miagao, finished the construction of our church in 1731 so that the Spanish priests from Oton would finally come to serve the religious needs of this town. In the year of our Lord 1741, the raiders came. They raped, killed, looted and burned our church!

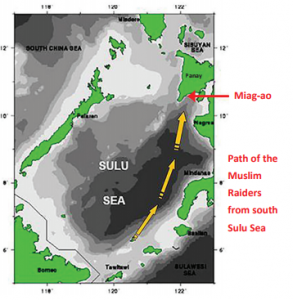

Six years later, in the year of our Lord, 1747, the raiders came back again and burned the second church built by Fray Fernando Camporedondo. Forty days each year men sweated carrying stones and timber for that church. Everyone 16 years of age to 60 must serve this forced labor called polo y servicio, except the town principalia, the Spanish Insulares and Spanish Peninsulares. The rich Indios, not many of them in town, pay the falla of seven pesos to be exempted. It is May 7, 1754. I am 23 years of age. I am standing guard on top of Cotta, the watchtower in sitio Baybay. I am just a comisario, a minor clerk in the office of the capitan, but now carrying a spear and a bolo strapped to my waist. We were rushed to Cotta two nights ago. The governadorcillo expected raiders to come from Sulu Sea any time soon. There are 30 of us inside Cotta. The walls of coral stones are 5 meters high, with wooden planks as palisades to protect us from flying arrows and spears. I have never fought anyone, never hurt anyone. The same goes for most of the men inside Cotta, except the cabeza de barangay of Baybay, Nong Fermin. He is much older than us. He wears a long sleeved shirt even in hot summer days, perhaps trying to hide the tattoos all over his body. Nong Fermin was and still is a Pintado. And, he seemed to have some experience in this sort of thing.

He came from beyond the sea one day about 30 years ago, married a local woman, says very little and keeps to himself most of time unless he needs to bark an order. Today, he is carrying a mysterious wooden case, about a meter long. All of us are afraid of him as much as we are afraid of the Moros. People say Nong Fermin was also a warrior decade ago. He fought in an army composed of Cebuanos and Ilonggos called Armada de los Pintados, the Army of the Painted Ones. This army, they say, crossed Sulu Sea on war boats called caracoa to raid the coastal Muslim villages of Zamboanga, Jolo and Basilan. The raiders coming today are Muslims from the far end of Sulu Sea, perhaps from the same villages previously raided by the Armada. Now they are back to do the same. I was also told that my great grandfather was also of the Muslim faith until Augustinian friars and Spanish soldiers with armor and firearms, the Conquistadores, came to our island of Panay to make him a Christian and take his land. It was convert or die—only two options. Is it right to call the Moros pirates when our Spanish ‘masters’ did the same to us? If we are not Christians, would the raiders still come? Had the Spanish not raided their villages, might they be civil and leave us alone? Or is it simply that they prefer the life of piracy as a tradition?

photo from philippineamericanwar.webs.com

Does the Moro I will face in battle today think about these things as well? I ask myself these questions as I look out to the horizon. Maybe one day I will have a chance to speak to a Moro and ask him, if he doesn’t kill me first. The raiders seem to come every 6 years during amihan, when the trade winds are favorable. My daydreaming was cut short by men shouting. The watchmen on the hilltop of Sitio Barangit-itip are signaling with mirrors. They have sighted twenty one sails over the horizon! Twenty one boatloads of angry Moros. Bells are ringing, sounds of drums made from hollowed-out tree trunks warning the people beyond the hills about the impending attack. I see throngs of women from the sitios of Baybay, Ubos and Kirayan, running with children in tow, carrying whatever they can of their meager, yet precious belongings, scurrying towards the sitio of Mat-y and the hills beyond. All the able bodied men are being herded, reluctantly up to Tacas by quadrilleros. The men in the watch towers of Kadamisolan and Kirayan are being withdrawn back to town to join the improvised ‘army’ of more comisarios, quadrilleros and a motley group of mostly simple farmers, laborers and traders armed with whatever they can find. The skirmish line is being formed in Tacas. The Spanish officer, Jose Echevaria, is busy ordering the company of men he brought along with him in a firing line with flintlock muskets while at the same time keeping the rest of the people’s army of reluctant Indios from running away in fear. There is capitan Agustin Gayo translating for the Spanish, trying to inspire the terrified folks to stand and fight.

We Indios, are descendants of the warlike Pintados! We have the blood of raiders in our veins too. I ask my self often, “Did turning into Christians also turn us into scared lambs? What happened to our forefathers that allowed us to become Indios only fit for polo y servicio for the Spanish and meat for the slave market of the Moros?

Then, there is the Spanish priest, Reverend Father Pedro Alvares, wearing his cassock giving God’s blessings to those about to die. How about us here in Cotta? No officer, no muskets and no priest on this miserable pile of coral rock. Today, many will certainly meet God because for the first time we are not running away in fear of the Moros. Well at least not yet.

Tacas is more defensible. It is uphill from the beach–a plateau. And the defenders of Tacas have moved farther into the reverse slope of the plateau, away from my sight and from that of the raiders. The messenger from Echevaria, almost breathless from the fast run downhill, arrived with a message from Tacas. He said, The Moros will likely go up the hill on the main road from the beach of Baybay.

We are the only force blocking their way. The raiders will try to destroy Cotta first to clear the road uphill. The Moros will not bypass us to

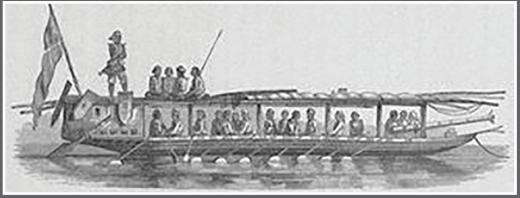

Depiction of the Visayan Pintados from boxer codex

go around. The messenger said, “You are ordered to defend Cotta for at least one hour to give Echeveria enough time to position the men for the counterattack.” That only means to me that Cotta is the bait for a trap. And, baits are always bitten or eaten by the beast we intend to trap. We at Cotta are the expendable bait! Bright red banners are strung up high on bamboo poles around Cotta. I asked, “What is that for?” The messenger said, “Remember the angry bull? Just making sure the Moros only see Cotta and head straight for you!” I see the vintas and the large raider boats they call caracoa. I can hear the faint beating of their drums and mesmerized by synchronized splash of oars on the sides of the long boats. The taunts from the boats are getting louder and louder each second. I can see the glint of the swords and the tip of their spears. Each caracoa can hold more than 80 warriors and there are at least ten of them heading directly to Baybay. The vintas are smaller and lighter, with the amihan winds pushing their sails faster, onwards towards shore. Each vinta can carry 5 men. We are facing about 1,000 warriors against 30 of us on top of Cotta. And, another group of 20 trembling men that came with the messenger, placed in hiding at the back palisades protecting our rear.

Fifty men. I hope Echevaria knows what the hell he is doing. I hope he has a cannon and the Spanish cavalry hidden up there in Tacas. The boats reached the beach almost simultaneously. The Moros have landed. Without even a pause, they scampered out of the boats, running like mad men towards the Cotta, some brandishing their swords above their heads, shouting insults. Most have wooden, intricately carved, colorful shields. I see no one carrying muskets. No lantaka swivel cannon on any of the caracoas. They have about 150 meters of beach to cover before they reach Cotta.

Now, I have the Moros in front of me. The shouts are deafening. Fear of the Moros can be so overpowering, so pervasive. I looked at my fellow comisarios to my left and to my right. The same fear in their eyes. Others are silently praying to Nuestra Senora de la Paz, the patroness of peace of Baybay. Nong Fermin shouted final instructions how we will fight as a group today. 30 meters. I can see their faces now–faces full of hate, rage and joy of finally being in personal combat soon. These are the faces of real, hardened, merciless warriors. Most are brandishing the sword called barung, not kampilan. The barung is the preferred sword of the Tausugs. They are thirsty for blood. Spears are thrown at us, most embedding themselves on the palisades with a loud thud. Over our heads, arrows are flying. Our bodies, pressed against the inside wall of Cotta, are hidden from view by the thick wooden palisades. I can hear my heart pounding! Screams of pain from the left and the right of me. An arrow embedding on one’s chest is a sound I have never imagined to be so bloodless but so palpable, so frightening.

Caracoa war boats on a raiding expedition. Rowers are on the outriggers. Estimated speed 16 knots, with rowers being exchanged periodically by those on the boat. Original watercolor from collection of Jonathan R. Matias (New York).

Prau of Illanoan pirates of Borneo and Sulu Archipelago. No outriggers, oars manned typically by slaves. lantaka canon on the bow of the boat and an upper deck for more warriors; capacity 80 warriors. Image from http://www.gutenb erg.org/

The two typical war canoes – the outrigger type caracoa and the prau –

likety seen from the beaches of Miag-ao during Salakayan

The bamboo ladders are now against the Cotta’s wall and the first of the Moros are on their way up shouting ‘Allah Akbar.’ Others are prying loose the mortars of the coral stones and inserting spears in between to create a makeshift ladder. I have thrown the first spear down towards them. I did not bother to look if it connected with someone’s flesh and bone. I just turned around to grab the next spear from the panicking spear bearer behind me. Shouts, screams, smoke and utter bedlam. Swords, spears, bayonets and bodies pressed against each other in the bloody mess of close combat on top of Cotta. This is going to be the longest hour of my life. SALAKAYAN has begun!

excerpts from the writings of

Jonathan R. Matias

Sulu Garden, Miag-ao, Iloilo

www.sulugarden.com